By Hunter Loren

Since the popularization of social media, a perceived feeling that history is essentially happening “faster” today compared to previous eras has been prevalent. After all, modern humans have existed for roughly 100,000 years. By 10,000 BCE, 90,000 years later, the Neolithic revolution began. Afterward, mankind progressed towards industrialism by the early 1800s: roughly 10,000 years later. It took only another 150 years to progress towards atomic power, and the information age was reached 50 years later. Indeed humanity is progressing faster than ever before, and this trend is likely to continue. Given such rapid progress, has the frequency of major world events truly accelerated in tandem with our transition to modernity? Or is the notion of history going faster simply an artifact of memory?

On August 7, 1945, American newspapers mostly featured two large headlines. One was the bombing of Hiroshima, and the other was the death of Major Dick Bong; a 24-year-old fighter pilot, and highest-scoring U.S. fighter ace of World War II. Most people have probably heard of one of these events, and consider it to be important. The other event is probably so obscure that one might for a moment think I am making up the name “Major Dick Bong” and saying that it was treated with co-equal importance to Hiroshima. And to be sure, even in its immediate aftermath, the death of Major Bong was in a somewhat smaller typeface than Hiroshima — but it was still a relatively big announcement – it was important news of the day according to the people. Read any old newspaper, and you’ll find many “major events” neglected today because they didn’t add up to much later. Hiroshima maintains its status as a major event because it is a symbol of an entirely changed world. Major Bong’s death did not. A similar story applies to most of human history. Every part of the world has had its fair share of major events in every century, every decade, and every year. To the average person, however, a time period such as the Medieval Era, for example, may only conjure thoughts of the Crusades or knights in shining armor, making such a complex time period seem like a blur with only a few major happenings. Other major events of the time such as the Treaty of Verdun, which foreshadowed the formation of the modern countries of Western Europe, or the Abbasid Revolution which shifted the Islamic world’s foci towards Baghdad are an afterthought, if a thought at all. Many major events in history are today relegated to the minds of historians, which inherently begs the question, “what about major events today?” After all, it’s not unlikely that hundreds of years in the future, major events which shook today’s world such as the women-led regime protests in Iran won’t be common knowledge among the average person, regardless of the impact they made on the world in 2022. Could this perceived increased frequency be a case of recency bias?

Of course, “major world events” have many variables. For the sake of simplicity, this brief analysis will consider a major world event as something that is genuinely counted as international news, having a ripple effect in its occurrence beyond a small region. Examples include wars, pandemics, natural disasters, economic crises, political revolutions, etc. Modern examples include the COVID-19 pandemic, the 9/11 attacks, and the climate change crises. I will also be focusing on 1900 onward, as newspapers, telegrams, and radio enabled worldwide communication and news about various events.

Of the many innovations that define the early twentieth century, the most notable is the sheer speed in which communication took place. In 1900, though knowledge of major world events was surely widespread, one’s information of events of the time such as the Boxer Rebellion was largely limited to coverage of local newspapers or word of mouth. In contrast, nearly all events in our modern world are considered “news”, with widespread media coverage not just through television programs but also social media. This means that the average person consumes news articles and sees some sort of notification about some sort of event whether they actively seek to do so or not. Because we don’t actively seek information, but can easily stumble across it regardless, it creates a seeming acceleration of events which can alter our perception of history (Rosa 2003). This amplification of news to the average person may also in turn lead to amplification of reactions to such events. In 1982, an upward estimate of 10,000 marched across Britain protesting the Falklands War (Peace Pledge Union 2012). Pushing for a ceasefire and negotiations, such marches were almost entirely limited to Great Britain. During the Breakup of Yugoslavia from 1992-1995, anti-war demonstrations were for the most part limited to the boundaries of what was once Yugoslavia, even as Western States directly intervened with NATO bombing campaigns or after news of the Srebrenica Massacre came to light. These wars directly involving major powers went down in history as primarily a regional issue. Decades later, the murder of George Floyd sparked outrage across the United States which almost immediately spread across the world and prompted Black Lives Matter demonstrations to be seen in every continent. What may have been an isolated incident just a few decades ago became a major world event through its coverage. If social media existed during the Falklands War or the Yugoslav wars, it’s certainly possible that these regional conflicts would have engendered a much broader reaction. Along with media prevalence enhancing knowledge of world news, the phenomenon of globalization within the last few decades has created vastly different dynamics in which the world operates. Economies and trade are more intertwined than ever before, and global interdependence creates a ripple effect in state economic downturns, amplified much more than in previous eras (Haldane and May 2011).

Perhaps the phenomenon is an artifact of memory or perhaps it’s simply a matter of exposure. Wars happen just as they did a century ago, as have religious conflicts and societal change. With increased exposure to major world events, a perception that more things are happening in the world is understandable. However, these kinds of events were still happening a hundred years ago. In describing how technology, mainly social media, is a primary culprit for amplifying worldwide events, I showed how it can morph what would otherwise be a regional issue into a much larger phenomenon. In a way, that means that it essentially makes new history. The transition to modernity has meant that as the world becomes more interconnected, so does the news. History may not be happening more often in terms of how many events actually happen, but technology has more so made new ways for history to happen and for news to reach all parts of the world.

Hunter Loren is a Political Science/Economics major from Great Neck, NY. After his undergraduate years, he aims to pursue a masters degree in International Relations. Building on previous experience in IR tutoring, Hunter intends to shed light on happenings in more unknown parts of the world. When he was nine years old he had an email correspondence with the president of Lithuania and he enjoys motorsports, baseball, and guitar.

References:

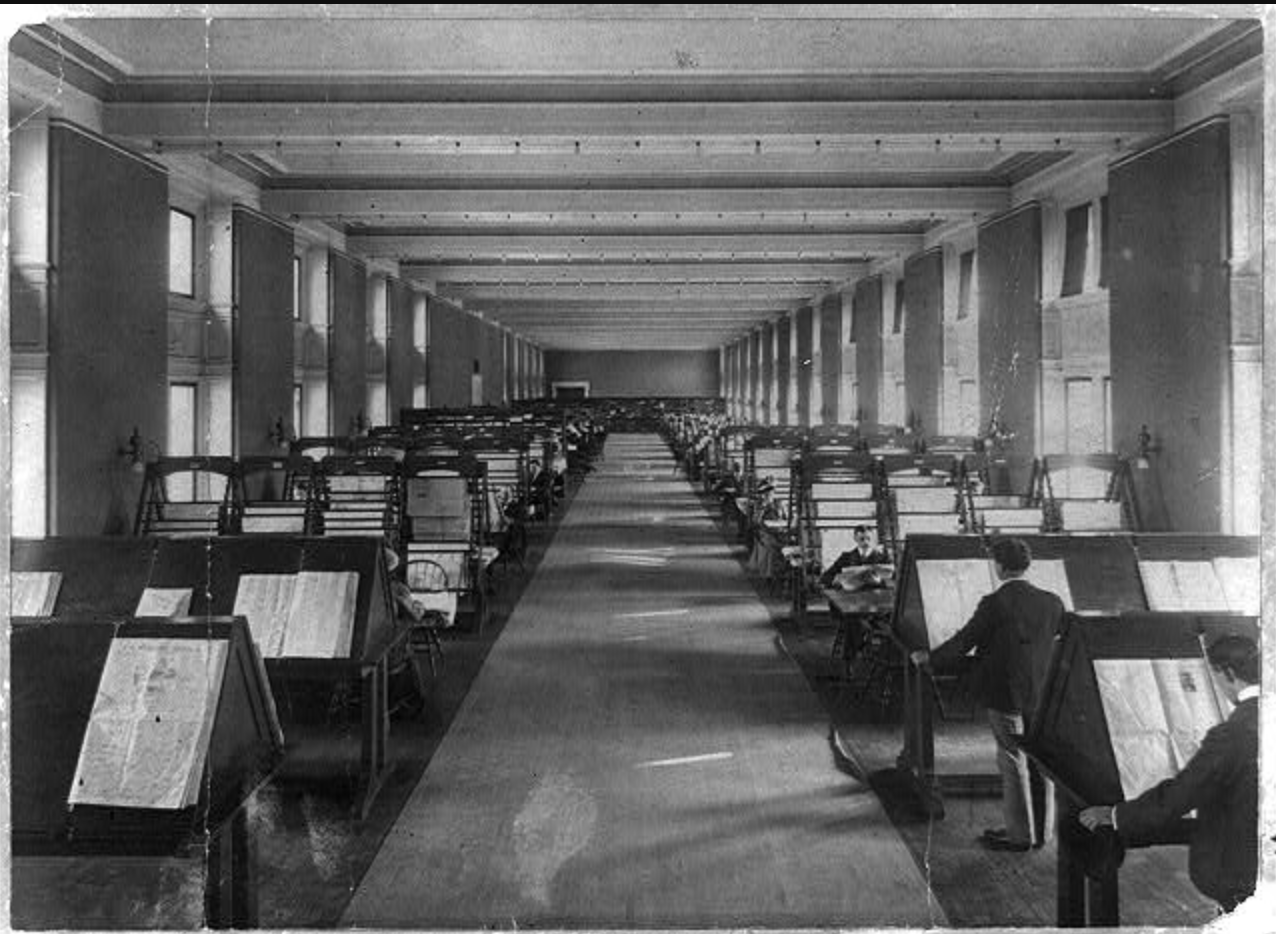

Photo credit: Photograph of the Newspapers & Current Periodicals Reading Room, Library of Congress. , 1900. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002716645/.

Haldane, Andrew G., and Robert May. 2011. “Globalization and Systemic Risk.” Nature 469 (7330): 351–355, January 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09659.

Peace Pledge Union. 2022. “Falklands War: 40th Anniversary.” Peace Pledge Union. https://www.ppu.org.uk/falklands40.

Prosic-Dvornic, Mirjana. “Enough! Student Protest ’92: The Youth of Belgrade in Quest of ‘Another Serbia’.” University of Belgrade. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/aeer/article/download/596/698/0

Rosa, Hartmut. 2003. Social Acceleration: Ethical and Political Consequences of a Desynchronized High–Speed Society. Constellations 10 (1):3-33. https://acceleratedclassroom.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/social-acceleration.pdf

Wellerstein, Alex. 2013. “Major Bong’s Last Flight.” Nuclear Secrecy Blog, August 6. https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/2013/08/06/major-bongs-last-flight/.

You must be logged in to post a comment.