By Chase Quinn, Elections

The United States prides itself on democratic and egalitarian values. Despite this, we choose to elect our executive by means of an Electoral College, which due to its nature, sometimes produces antimajoritarian election outcomes. These results go against the wishes of a majority of voters. This is easiest explained by looking at the popular vote in our presidential elections. Since the founding of the country, anti-majoritarian results have happened a total of five times in our presidential elections. The two most recent were in 2000 and 2016. In 2000, Al Gore lost the election to Geroge W. Bush despite winning the popular vote by over 500,000 votes, while Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump in 2016 despite winning 3 million more votes than him (American Presidency Project 2024). Both are cases in which candidates won the presidency despite winning less votes than their opponents. The other three antimajoritarian elections were in 1824, 1876, and 1888.

Margins for the 1984-2020 presidential elections are shown in Figure 1, with graph color corresponding to the winning party for that year’s election. Margins represent the amount of votes that a candidate won or lost the popular vote by. A negative margin represents candidates that won the election despite losing the popular vote.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

In a comparative sense, the electoral college is an institution very specific to the United States. No other country in the world uses a system like this to elect their executive office, instead using direct elections (Sacher 2024). Contrary to popular belief, in the United States we do not directly elect our president, the electoral college does. Proponents of reform argue that utilizing a direct election method would be more democratic, as it would utilize a “one person one vote” framework where each individual vote is truly considered equal and not affected by the state where one lives. To illustrate this, we can look at the proportion of electoral college votes to state populations.

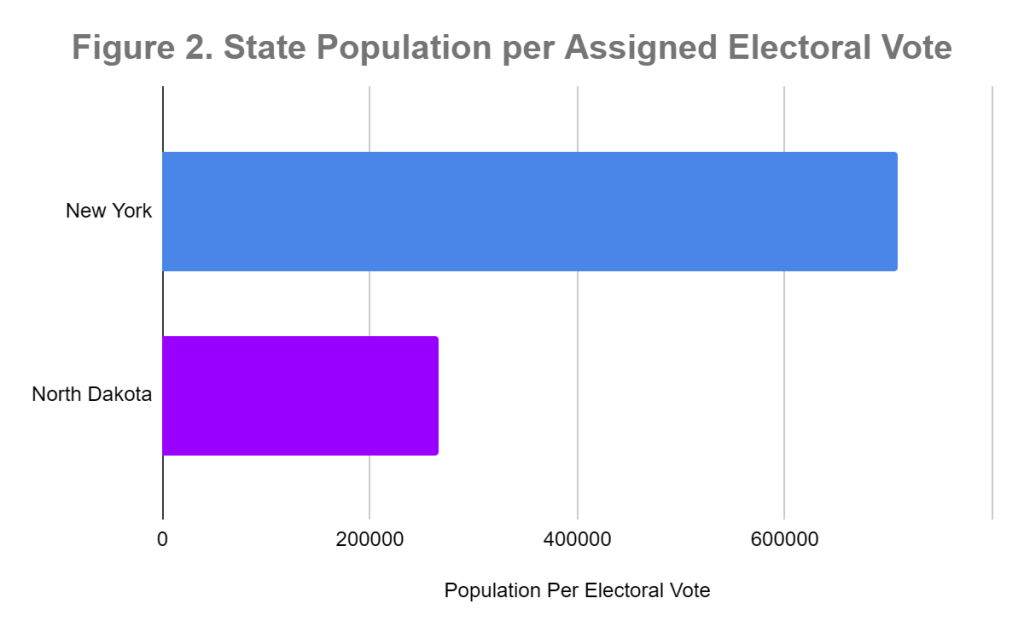

Advocates of electoral college reform point out that the weight of individual votes differs between states and disproportionately benefits states with low populations. Take for example North Dakota, the fourth least populous state, compared with New York, the fourth most populous state. North Dakota has a total of 3 electoral college votes, while New York has 28.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.census.gov/popclock/

A simple calculation of the proportion of population to electoral votes in each state shows some discrepancies, shown in Figure 2. Despite the drastic difference in populations, individual votes have much less weight in New York than they do in North Dakota. For every electoral college vote assigned to North Dakota, there is a population of 265,523 individual voters, more than half of the amount it takes in New York of 709,445 individual voters per electoral vote assigned. Individual votes in more populous states are given less weight than those in less populous states, despite the fact that populous states make up a greater proportion of overall population and thus represent more people. For reference, comparing state populations to the total population of the United States, New York makes up 5.7% of total population while North Dakota makes up only 0.23%, showing that New York has 25x more people than North Dakota. Electoral college votes are assigned to states based on proportion to population, but the minimum number of votes assigned to each state is three. If this minimum were to be removed, sparsely populated states like North Dakota would have less than three electoral votes as they represent proportionally much less people than populous states.

Nullified Votes and Safe States

Another criticism of the electoral college is that it routinely renders large proportions of the country’s vote to be null and void. If you are a Republican living in a heavily-leaning Democratic state, for example, your vote in the Presidential election is essentially meaningless. Every election your vote is cast, but it makes no dent on the overwhelming state majority that votes Democrat, giving all of your state’s electoral votes to the opposing party and rendering your vote as having essentially no effect on the race.

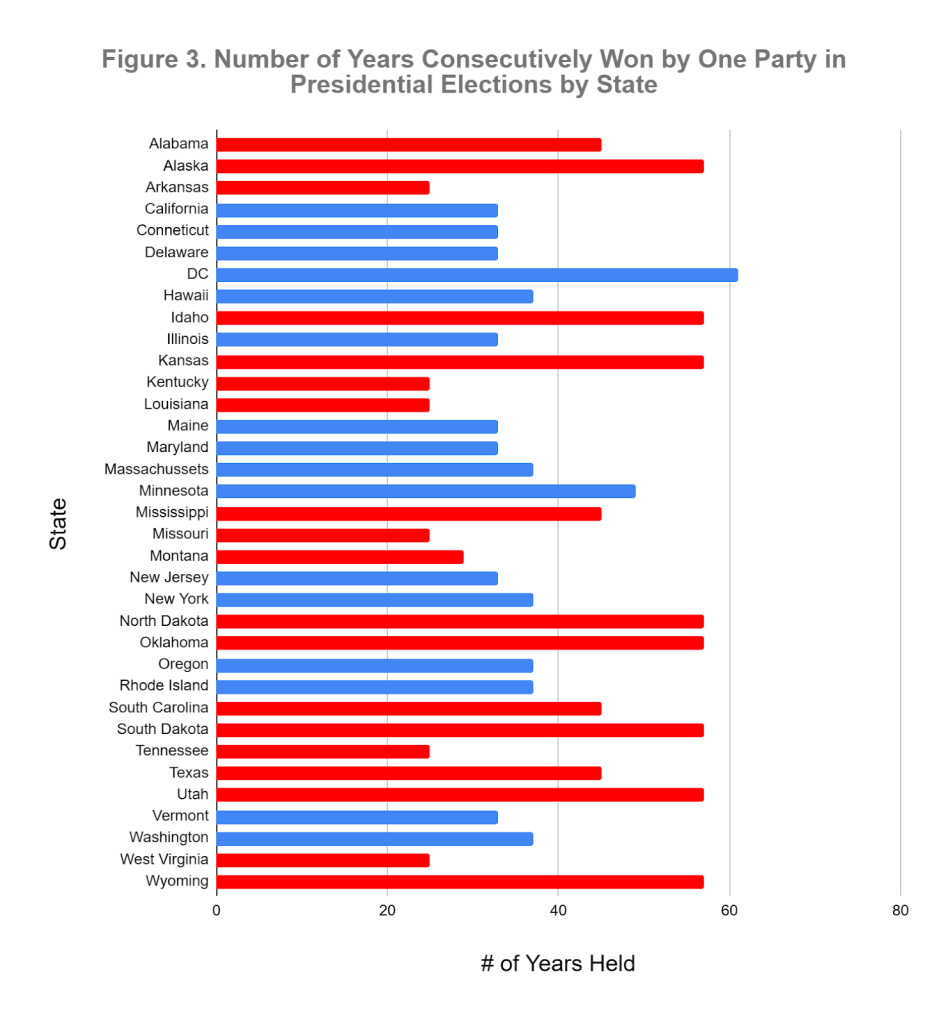

This is an especially prevalent issue in political “safe” states. These are states in which political beliefs stay relatively stable, and in which the same party has stayed dominant for an extended amount of time (in this case for 20 years or more). Alaska is a great example of this. For the past 15 presidential elections Alaska has voted Republican, marking a 57 year long period where the majority of voters have not changed their general political stances. If you are a Democrat or align with any other party in Alaska, however, your vote has been considered meaningless for the last 57 years, as a vote that does not produce any electoral college votes is useless in the overall election. Figure 3 shows the number of years that different states have been consecutively under one party control in presidential elections. This data only includes politically safe states and excludes swing states. Each state is color coded by the party in control. Note that despite not being one of the 50 states, DC is included as it is given three electoral votes and treated as its own electoral entity under the 23rd Amendment.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

This is an issue that ascends partisanship, with nullified votes happening to both Democrats and Republicans as well as third parties across the country on every presidential election. The electoral college thus puts a heavier emphasis on swing states, which have very close margins and are easier to flip from party to party. As such, swing states are high priority targets for presidential campaigns, as flipping a single state could mean victory. Political competition has shifted to swing states so much that politically safe states have been observed to have lower voter turnout than swing states. During the 2016 election, 80% of states labeled “battleground states” by NPR reported higher voter turnout than the national average (Kurtzleben 2016).

Voters in noncompetitive states face a dilemma. For example, say you are an Alaskan Republican voting in the 2028 presidential election. Alaska has voted Republican for 57 straight years and is very likely to vote Republican again. You’re satisfied with the results, but why bother going to the polls if you know that your party is going to win anyway? In the same vein, if you are a Democrat or third party voter in Alaska, it seems hopeless to cast a vote in an election that seems to be lost from the get go. On either side of the aisle voters are discouraged from casting their votes, leading to less political competition and less representation.

Reform

Examining issues like this then begs the question, why do we still have the electoral college? In widespread national studies, polling has consistently shown that a majority of voters would prefer to see the electoral college removed and replaced by a national system of voting, similar to how other countries do it. A 1981 national poll found that 75% of Americans favored the abolition of the Electoral College (West 2020). Over the years, however, sentiments have been changing, with new trends emerging among partisans. Despite this, there is still a majority of support in favor of doing away with the Electoral College. A more recent Gallup survey done during the 2000 Presidential Election found that 73% of Democratic respondents supported abolition, while only 46% of Republicans did as well (West 2020).

Abolition of the Electoral College faces two major issues: conflicting interests, and unanimous consensus. The main way to realistically reform our Presidential voting system would be to pass a constitutional amendment, which requires a very strong consensus of at least two-thirds of both chambers of Congress. While it is not entirely unrealistic, it is definitely difficult. Even if a reform bill manages to pass this threshold, it must also be ratified by at least three quarters of states to be considered valid. Past measures to do away with the electoral college have come close to success, but ultimately failed, such as an attempt done in 1969-1970 (Silva 2013).

Then there’s also competing political interests. Both dominant parties in the United States benefit from the electoral college to some degree. In politically safe states, the electoral college provides an easy way to gain votes while nullifying those of the opponents. Candidates can rely on safe states for large amounts of their electoral votes and focus on fewer crucial swing states to try and win the election. Remember from Figure 3, a majority of states are considered politically safe and political attitudes typically change little from election to election. The electoral college also makes the political system less competitive considering the possible impact of third parties on elections. It’s extremely difficult for third parties to gain any sort of traction in a national presidential election because they face such high thresholds to secure electoral votes. The last time a third party candidate won any states was in 1968, when George Wallace won 46 electoral votes running under the American Independent Party, but even he was still far from victory (The American Presidency Project n.d). Democrats and Republicans both benefit from this effect, as it keeps competition from additional parties essentially nonexistent.

As a result of these factors, there’s conflicting motivations for current party politicians to advocate for reform. And with politics becoming increasingly polarized between Democrats and Republicans, they probably have other things on their minds besides abolishing the electoral college.

Chase Quinn is a senior at Binghamton University serving as the elections reporter. He studied journalism at Hunter College for two years before transferring to Binghamton to pursue a bachelors in Political Science and Master’s in Public Administration. He was born and raised in the town of Pine Plains, New York. Post-college he plans to conduct research on policy and law and aims to work in the public sector. In his free time, Chase likes to read, spend time outdoors, create art, and make jewelry.

References

Woolley, J. T., & Peters, G. (2024, November 6). Presidential election margin of victory. Presidential Election Margin of Victory | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/presidential-election-mandates

Woolley, J. T., & Peters, G. (n.d.). 1968: The American presidency project. 1968 | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections/1968

Sacher, J. M. (2024, September 16). Why does the U.S. still have an electoral college?. University of Central Florida News. https://www.ucf.edu/news/why-does-the-u-s-still-have-an-electoral-college/

Silva, R. C. (2013, September 2). The Lodge-Gossett resolution: A critical analysis: American political science review. Cambridge Core. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/abs/lodgegossett-resolution-a-critical-analysis/98DF1DCFC665D06C399A6D64C1DBBDB6

Kurtzleben, D. (2016, November 26). Charts: Is the electoral college dragging down voter turnout in your state?. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2016/11/26/503170280/charts-is-the-electoral-college-dragging-down-voter-turnout-in-your-state

West, D. M. (2020). It’s time to abolish the Electoral College Policy . Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/big-ideas_west_electoral-college.pdf

Population clock. United States Census Bureau . (n.d.). https://www.census.gov/popclock/

Election results and voting information. Federal Elections Commission . (n.d.). https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

You must be logged in to post a comment.