-

Cooperation and Contention: The Dynamic Relationship Between the United States and China

By Alyssa Hazen, US Policy

The United States and China have one of the world’s most complex relationships. The two countries have experienced periods of tension and cooperation over a range of issues. Key areas of conflict between the two include trade and economic practices. While the US and China have a critical trade relationship, they are also major competitors. The US has cited China’s economic policies as a point of contention, finding that the country’s practices related to trade and labor pose a threat to the United States’ own economic and security interests (US Government Accountability Office). This has led the US to take action against China, primarily through the imposition of tariffs, and China has shown retaliation in return. Despite tensions, the two countries remain economically connected—intertwined in a relationship that is crucial to the global economy.

US Tariffs

Since the inauguration of President Trump under his second term, the administration has made it a priority to impose tariffs on imports from other countries. The Trump administration’s economic policy is designed to protect domestic industries and American workers, address the trade deficit, and raise government revenue. In the first month of his presidency, Trump imposed tariffs using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). He declared that the threat posed by the flow of illegal immigrants and drugs from Mexico, Canada, and China constituted a national emergency under the act (White House 2025). The administration imposed a 25% additional tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico and a 10% additional tariff on China (White House 2025). The tariffs were established as a means of holding the countries accountable to their promises on curbing illegal immigration and stopping the flow of drugs into the US. The administration argued that the tariffs are a way to protect the United States’ national interest and security, as well as the safety of American citizens. Trump imposed further tariffs in April. Once again using the IEEPA, Trump declared that foreign trade practices constituted a national emergency. The administration issued a 10% tariff increase on imports from all countries, arguing that this was necessary due to the threat posed by the trade deficit and lack of reciprocity in trade relationships (White House 2025). The administration highlighted China’s non-market policies, in particular, arguing that these policies gave China global dominance. This had repercussions on the US industry and trade deficit, leading to job losses and a national security threat as a result of an increased reliance on foreign supply chains (White House 2025).

During April, the Trump administration’s tariffs caused increasingly more conflict between the US and China. Under US Section 232, a provision in the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, the president can adjust imports that threaten national security. Under this provision, Trump imposed tariffs on steel, aluminum, and automobiles. These tariffs were an effort to counter the flood of these materials from China in global markets (Peterson Institute For International Economics 2025). Following the implementation of these tariffs and those imposed under the IEEPA, US tariffs grew to 145% on all imports from China as of April 11th. In retaliation, China’s tariffs on US imports rose to 125% (Council on Foreign Relations).

China’s Response

China responded to the United States’ tariffs by means of retaliation. While China imposed tariffs back at the US, its primary mode of retaliation took the form of depriving the US of investment. China, which is dependent on soybean production from other countries, imports three-fifths of soybeans traded in the global market (Bradsher 2025). Since late May, China had been boycotting purchasing soybeans from the United States, in response to Trump’s tariffs. Last year, China had exported $12.6 billion worth of soybeans, but as of late September, this has entirely dropped (Draper 2025). In retaliatory tariffs, the total duties that China imposed on US grown soybeans reached 34% (Rappeport 2025). This has caused a severe strain on American farmers, who are running out of space to store soybeans as well as facing financial struggles as a result of a declining export rate.

In addition to boycotting the purchase of American soybeans, China also deprived the US from investing in its rare earth metals. China curbed exports on rare earth metals in October, in an attempt to claim more control over the manufacture of technology (Bradsher and Tobin 2025).

Rare earth metals are essential in the production of computer chips, magnets, and the systems in cars. Many major US-based companies, such as Nvidia and Apple rely on the export of these metals to manufacture their products (Bradsher and Tobin 2025). Limiting exports of these rare earth metals would allow China to exploit the dominance it has over this sector and compete with the United States’ leadership in the global technology market.

Deal Making

Both the United States and China threatened to raise tariffs exponentially in the months immediately following Trump’s inauguration, but extended a truce until November to facilitate deal making. In late October, Trump met with China’s President Xi Jinping. The two leaders reached a trade deal that ensured the protection of the United States’ national security and workers, in addition to lower tariffs imposed upon China (White House 2025). Under the deal, China is to suspend export controls on rare earth metals, reduce the flow of drugs into the US, suspend its retaliatory tariffs, and resume exporting American soybeans. In return, the US is to curb tariffs imposed on China and extend the expiration of investigations into China’s unfair trade practices (White House 2025).

Conclusion

The relationship between the United States and China continues to be defined by a balance between economic interdependence and strategic rivalry. Tariff escalations under the Trump administration showcase how quickly tensions can rise when one country’s trade and economic practices are framed as a threat to another’s national security interests. As both nations imposed increasingly severe measures, economic costs mounted on both sides. Yet, despite these tensions, the willingness of both countries to negotiate a deal underscores the importance of cooperation between major world powers in maintaining global stability. While conflict remains a persistent characteristic of the United States’ and China’s relationship, methods of resolution exist when economic interests are at stake for both sides. The United States and China are bound by an interdependent economic system that requires cooperation despite contention.

Alyssa Hazen is a sophomore and political science major from Brooklyn, New York, as well as an Associate U.S Policy Reporter at Happy Medium. She plans on attending law school after graduating from Binghamton and hopes to pursue a career in corporate law. She is most interested in studying the intersection of politics and the environment. In her spare time, she enjoys reading and playing the guitar.

References

Bradsher, Keith. 2025. “In Tariff Standoff With Trump, China Boycotts American Soybeans.” New York Times. September 4 https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/04/business/china-soybeans-trump-tariffs.html?searchResultPosition=2

Bradsher, Keith and Meaghan Tobin. 2025. “China Clamps Down Even Harder on Rare Earths.” New York Times. October 9 https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/09/business/china-rare-earth-exports.html

Council on Foreign Relations. 2025. “U.S.-China Relations.” https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-china-relations

Draper, Kevin. 2025. “China Bought $12.6 Billion in U.S. Soybeans Last Year. Now, It’s $0.” New York Times. September 25 https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/25/business/china-soybean-sales-farmers.html?searchResultPosition=3

Peterson Institute For International Economics. 2025. “US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart.” November 10 https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2019/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-date-chart

Rappeport, Alan. 2025. “China’s Snub of U.S. Soybeans Is a Crisis for American Farmers.” New York Times. September 15 https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/15/business/china-us-soybeans-farming.html?searchResultPosition=4

The White House. 2025. “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Imposes Tariffs on Imports from Canada, Mexico and China.” February 1 https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-imposes-tariffs-on-imports-from-canada-mexico-and-china/

The White House. 2025. “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Declares National Emergency to Increase our Competitive Edge, Protect our Sovereignty, and Strengthen our National and Economic Security.” April 2 https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/04/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-declares-national-emergency-to-increase-our-competitive-edge-protect-our-sovereignty-and-strengthen-our-national-and-economic-security/

The White House. 2025. “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Strikes Deal on Economic and Trade Relations with China.” November 1 https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/11/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-strikes-deal-on-economic-and-trade-relations-with-china/ U.S. Government Accountability Office. “U.S. – China Relations.” https://www.gao.gov/u.s.-china-relations

-

Deportations for Tariffs: How the Trump Administration is Using Foreign Policy to Achieve Domestic Goals

By Ameen Kimdar, US Policy

Deportations and tariffs have been on the top of the agenda for the White House since the beginning of the second Trump administration in January of this year. Running on a campaign of populism and nationalism, Donald Trump promised supporters that the United States would make a show of strength by forcibly removing foreign nationals from the country by any means necessary and by putting an end to “unfair” trade deals that benefited foreign countries more than the US. Prior to entering office, experts anticipated that Trump’s foreign policy would be based on a reciprocal approach to diplomacy, viewing relationships as “transactional” (Cha 2024). Both policies, mass deportations and protectionist trade policies, have become intertwined tools in a larger strategy of coercive diplomacy. In particular, the administration’s usage of third-country deportations, the practice of deporting individuals to a country that they have no connection with, demonstrates how immigration enforcement has become a bargaining chip to achieve goals in trade policy and other foreign policy areas that the US has an interest in.

The White House has leveraged tariff threats and other intimidation tactics to persuade smaller, often-aid dependent developing nations in Latin America, Africa and Asia into accepting deportees from countries unrelated to their own. Likewise, cooperation on deportations has been used as a precondition for favorable trade terms and tariff exemptions. This practice has drawn controversy within the United States from migrant rights organizations and from countries that have resisted or opposed becoming a “dumping ground” for immigrants. However, many countries have welcomed this approach to dealing with the US, and have leveraged their position as an easy way to get on the US’ good side in other areas such as trade policy.

During the first Trump administration, one of the largest challenges that ICE officials faced was deported migrants’ home countries refusing to accept their citizens back. In 2017, the US put visa restrictions on Eritrea, Cambodia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone for refusing to accept thousands of migrants that had been convicted of crimes in the United States and were sentenced to deportation. ICE officials claimed that sanctions were necessary to pressure these countries into accepting deportees out of US custody (Nixon 2017). Among other issues, the second Trump administration has taken a much more aggressive direction with achieving policy goals, and the introduction of third-country deportations have become a major part of its immigration policy.

Beginning at the start of Trump’s return to the White House, 5000 migrants were sent on military aircraft to Guatemala and Mexico (Stewart and Ali 2025), while Colombia’s left-wing president Gustavo Petro refused to accept what he described as “inhumane” treatment of migrants. After Trump threatened massive tariffs and visa suspensions on Colombia, Petro was forced to back down and accept deportations via military aircraft, as the US is the largest trading partner of the South American nation (Stewart and Griffin 2025).

In February, aggressive deportations escalated, with the first recorded instance of third-country deportations occurring in Panama and Costa Rica. Three flights carrying 300 deportees from Africa and Central Asia arrived in Panama, where they were first held in a hotel, and those who refused were sent to a prison camp in the jungle (Wong et al. 2025). Later that month, Costa Rica accepted 200 deportees from China, India, Nepal and Yemen (Wong et al. 2025). Almost all of the US deportees in Central America were later released and sent to their countries of origin after their lawyers sued the governments holding them (Wong et al. 2025). This occurred amidst massive pressure on Panama from Trump, who had publicly stated a desire to regain control of the Panama Canal, which had been returned to the small country in 1977 by Democratic president Jimmy Carter. Panama is an important destination for migrants crossing the Darien gap between South and Central America en route to the United States (Zamorano 2025).

One of the most publicized cases of third-country deportations occurred in the following month, when hundreds of accused Venezuelan gang members were sent to El Salvador’s infamous CECOT prison. Salvadoran president, Nayib Bukele, a close ideological partner with Trump, has garnered international attention for his extreme measures on gang violence, an issue that has plagued the nation for decades. On the other hand, Venezuela has severed ties with the United States since 2019, due to ideological differences and US support for the Venezuelan opposition. The US paid El Salvador roughly $6 million to host the alleged Venezuelan gangsters in their maximum-security prison, and invoked a “zombie” law from 1798 to authorize the decision, the Alien Enemies Act, which permits the president to deport noncitizens during wartime (Al Jazeera 2025). Venezuelan deportees were also accepted by Honduras, a country that has experienced strained relations with the US in recent years for its close relations with Venezuela. Honduran president Xioamara Castro had previously threatened to expel a US military base in the country over threats of mass deportations, but buckled under US pressure (Olivares 2025). Trump officials claimed that the migrants were a part of a criminal gang known as Tren de Aragua, which he has also accused of being tied to the Venezuelan government, which CIA and NSA sources have disputed (Olivares 2025). Among the deportees was Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran man living in the US legally, wrongfully deported in an “administrative error” (Al Jazeera 2025).

By summer, the third-country deportations expanded into Africa, where human rights groups have expressed the most amount of concern for the safety and wellbeing of migrants. In early Julyeight migrants convicted of robbery, murder, and sexual assault were deported to South Sudan that the State Department has listed as unsafe for American citizens to visit. Only one of the migrants was actually from South Sudan, while the rest were from Myanmar, Mexico, Cuba, Vietnam and Laos. This occurred after a legal battle while the migrants were being temporarily detained in a shipping container in the small African nation of Djibouti (Hagan 2025). Earlier, the Trump administration had revoked all South Sudanese visas and accused the world’s youngest nation of “taking advantage of the US” by refusing to take deportees (Al Jazeera 2025). The following week, the US deported five migrants convicted of crimes including child rape and murder to the tiny southern African country of Eswatini, despite all of the men coming from Vietnam, Laos, Jamaica, Cuba and Yemen. Commentators noted that Eswatini, an absolute monarchy with a poor human rights record, is dependent on the US for its largest export, sugar (Muia 2025). By August, deportations extended to Uganda, a country that had previously experienced strained relations with the US under the Biden administration for its anti-LGBTQ laws, and is also severely threatened by US sanctions on its agricultural exports (Lawal 2025). Rwanda, another African country with a poor human rights record, accepted seven US deportees from unrelated countries (Fleming 2025). Rwanda has cooperated with Israel and the UK on deportations, which was struck down by the UK Supreme Court over human rights violations in Rwanda (Sharma 2025). Nigeria, Africa’s most populated country, refused to cooperate on Venezuelan deportations, and was hit with visa restrictions, which the US embassy in Abuja denied was related to migration policy (Booty 2025). Later, Ghana accepted deportations of Nigerians, and denied they were being held in prisons in Ghana, rather they were sent back to their home countries (Riccardi 2025). On the other hand, Burkina Faso, which has become fiercely hostile towards the US in recent years, refused to accept any deportations on an ideological basis (Banchereau 2025). Outside of Africa, partially-recognized Kosovo has accepted 50 migrants, promising to return them home (Camilo 2025).

A New York Times investigation found that the State Department has approached 51 countries across the developing world to accept deportations in exchange for concessions in other areas, including foreign aid and trade policy. A State Department cable identified Angola, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Rwanda, Togo, Mauritania, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan as target countries for third-country deportations, in spite of abysmal human rights violations and civil wars occurring in most of these countries (Wong et al. 2025). Leaked documents showed the State Department pressured war-torn Ukraine into accepting third-country deportations as a part of conditions on receiving aid from its primary benefactor (Taylor et al. 2025). Prior to a White House meeting with leaders from Liberia, Senegal, Mauritania, Gabon and Guinea-Bissau, US officials requested that these countries cooperate with deportations, as these countries have been reeling from the consequences of the cancellation of USAID (Gramer et al. 2025).

The Trump administration’s usage of third-country deportations have become emblematic of its aggressive and transactional foreign policy, with countries gaining favorable positions on trade policy and their human rights records if they help Trump achieve his domestic goals. While some governments have resisted, it appears that they cannot afford trade wars with the US.

As previously mentioned, these deportations have faced several legal challenges and have garnered controversy by migrant rights organizations. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) allows the Department of Homeland Security to deport migrants to countries other than their country of origin, but the nature of these deportations have been challenged in court (Metzler 2025). Federal courts initially blocked the South Sudan deportations on the grounds that they were not protected from torture, but the Supreme Court allowed for the deportations to occur anyways (Charalambous and Garcia 2025). In another case, federal courts ruled that they were unable to prevent Trump from carrying out deportations to Ghana (Cameron 2025).

Another source of contention regarding third-country deportations is the necessity of the process altogether. Lawyers representing Mexican nationals deported to Libya and South Sudan claimed that the Trump administration never actually asked Mexico about accepting these deportations, which was corroborated by Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum (Cooke and Hesson 2025). They also noted that Mexico has accepted thousands of deportees in the past, implying that the home country governments of deportees are not being properly informed of deportations. They instead suggested that the intention of third-country deportations is to intimidate migrants into self-deporting to avoid being sent to a much more hostile foreign country. A similar view was expressed by Doris Meissner, former Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service under Bill Clinton, stating the reason for third-country deportations to be “fear and intimidation and ultimately, incentivizing self deportation” (Montoya-Galvez 2025).

In spite of legal challenges and human rights concerns, the Trump administration hasn’t slowed down the usage of third-country deportations. Instead, it has double downed on the as a deterrent and a display of strength, framing it as a restoration of American sovereignty. Supporters of the policy view it as a necessary move to correct what they view as decades of exploitation of the US in trade and migration policy by weaker countries. Critics view it as a deliberate violation of human rights and international norms to intimidate migrants into not entering the US and pressure foreign countries to accept US trade terms. Regardless of their true intentions and legal challenges, third-country deportations have become a major weapon of Trump’s coercive diplomacy.

References

Banchereau, Mark. 2025. “Burkina Faso Rejects Proposal to Accept Deportees from the US.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/burkina-faso-united-states-deportees-982e4a4645a78eed9603ac6a9d60f21d (November 8, 2025).

Booty, Natasha. 2025. “Nigeria Can’t Take Venezuelan Deportees from US, Says Yusuf Tuggar.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c23gz78v5jjo.

Cameron, Chris. 2025. “Federal Judge Declines to Intervene for Migrants Deported to Ghana.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/16/us/politics/judge-migrants-deported-ghana.html.

Camilo Montoya-Galvez. 2025a. “Kosovo Agrees to Accept U.S. Deportations of Migrants from Other Countries.” Cbsnews.com. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/kosovo-accept-u-s-deportations-of-migrants-from-other-countries/.

———. 2025b. “U.S. Broadens Search for Deportation Agreements, Striking Deals with Honduras and Uganda, Documents Show.” Cbsnews.com. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-deportation-agreements-honduras-uganda/.

Cha, Victor. 2024. “How Trump Sees Allies and Partners.” Csis.org. https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-trump-sees-allies-and-partners.

Charalambous, Peter, and Armando Garcia. 2025. “Judge Blocks Administration from Deporting Noncitizens to 3rd Countries without Due Process.” ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/judge-blocks-administration-deporting-noncitizens-3rd-countries-due/story?id=120951918.

Cooke, Kristina, and Ted Hesson. 2025. “The US Said It Had No Choice but to Deport Them to a Third Country. Then It Sent Them Home.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-said-it-had-no-choice-deport-them-third-country-then-it-sent-them-home-2025-08-02/.

Fleming, Lucy. 2025. “Rwanda-US Migrant Deal’s First Group of Deportees Arrive, Says Spokesperson.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ckg4xp2my0vo.

Gramer, Robbie, Alexander Ward, and Tarini Parti. 2025. “Exclusive | U.S. Pushes More African Countries to Accept Deported Migrants.” The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/u-s-pushes-more-african-countries-to-accept-deported-migrants-b6f330c5 (November 8, 2025).

Hagan, Rachel. 2025. “US Deports Eight Men to South Sudan after Legal Battle.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c80p315krr4o.

Lawal, Shola. 2025. “What Will Uganda Gain from Accepting US Deportees?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/8/23/what-will-uganda-gain-from-accepting-us-deportees.

Metzler, Jacqueline. 2025. “What Are Third-Country Deportations, and Why Is Trump Using Them?” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/article/what-are-third-country-deportations-and-why-trump-using-them.

Muia, Wycliffe. 2025. “US President Donald Trump’s Administration Deports Five Migrants to Eswatini.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/clyze8mvzdgo.

Nixon, Ron. 2017. “Trump Administration Punishes Countries That Refuse to Take Back Deported Citizens.” Nytimes.com. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/13/us/politics/visa-sanctions-criminal-convicts.html (November 7, 2025).

Olivares, José. 2025. “Venezuelan Immigrants Deported from US to Venezuela via Honduras.” the Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/24/venezuela-immigrants-us-honduras.

Riccardi, Nicholas, Chinedu Asadu, and Edward Acquah. 2025. “Ghana Says African Immigrants Deported by the US Have Returned Home.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/us-ghana-deportations-trump-third-countries-africa-efbec16e3725e3065b2578ccc7a175a2.

Sharma, Yashraj. 2025. “Is Trump Using Africa as a ‘Dumping Ground’ for Criminals?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/7/25/is-trump-using-africa-as-a-dumping-ground-for-criminals.

Staff, Al Jazeera. 2025a. “Can Trump Legally Deport US Citizens to El Salvador Prisons?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/4/16/can-trump-legally-deport-us-citizens-to-el-salvador-prisons.

———. 2025b. “Why Has Trump Revoked All South Sudanese Visas?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/4/7/why-has-trump-revoked-all-south-sudanese-visas.

Stewart, Phil, and Idrees Ali. 2025. “Exclusive: US Military Aircraft with Deported Migrants Lands in Guatemala, Officials Say.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-military-aircraft-with-deported-migrants-lands-guatemala-official-says-2025-01-27/.

Stewart, Phil, and Oliver Griffin. 2025. “Trump Heaps Tariffs on Colombia after It Refuses Migration Deportation Flights.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/colombias-petro-will-not-allow-us-planes-return-migrants-2025-01-26/.

Taylor, Adam, Sarah Blaskey, and Siobhán O’Grady. 2025. “Trump Team Urged Ukraine to Take U.S. Deportees amid War, Documents Show.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2025/05/06/trump-ukraine-deportees/.

Wong, Edward, Zolan Kanno-Youngs, Hamed Aleaziz, and Minho Kim. 2025. “Inside the Global Deal-Making behind Trump’s Mass Deportations.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/25/us/politics/trump-immigrants-deportations.html.Zamorano, Juan. 2025. “Nearly 300 Deportees from US Held in Panama Hotel as Officials Try to Return Them to Their Countries.” AP News. https://apnews.com/article/panama-trump-migrants-darien-d841c33a215c172b8f99d0aeb43b0455.

-

Trump Administration Opens Arctic Wildlife Refuge to Oil Drilling

By Abigail West, US Policy

Trump Administration Opens Arctic Wildlife Refuge to Oil Drilling

Photo credit: Vladimir EndovitskiyTrump announced in October that he would open the entire 1.56 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s Coastal Plain to oil and gas leasing. These lands are sacred to the Gwich’in Nation, home to irreplaceable wildlife, wilderness, and cultural values, and have never seen industrialization. The Secretary of the Interior, Doug Burgum, held a press conference in October to confirm that the Department of the Interior will open the Coastal Plain to maximum oil and gas development to benefit corporate polluters (EarthJustice 2025).

These action packages were designed to improve public health and safety for Alaskans, advance energy development, and revamp land and resource management across the state. Along with reopening the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the King Cove–Cold Bay Road corridor will be established via a land exchange, right-of-way permits for the Ambler Road will be finalized, and land allotments for eligible Alaska Native veterans of the Vietnam War will be offered (DOI 2025). The Amber Road permits are costly and have been opposed by 88 Alaska Native Tribes and First Nations, and will cause substantial harm to wildlife, including caribou.

Alaska’s Arctic warming is 3-5 times higher than anywhere else in the world, in a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. This accelerated warming is primarily due to the ice-albedo feedback loop, in which the Arctic loses its reflective ice and snow cover, allowing darker ocean and land beneath to absorb more heat, creating a cycle that drives faster warming (EPA 2024). This explanation means that Arctic oil drilling will have disastrous effects on Alaskans and countless other Americans. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is home to numerous animals, including providing essential habitat for species such as Porcupine caribou, denning polar bears, and other wildlife (Harvard, 2025).

In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) (NPS, 1980) designated 1.5 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Range, known as the Coastal Plain, for gas development. No lease sales were made until 2021, when Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017. This Act required the Secretary of the Interior to conduct at least two lease sales over 10 years. Under President Trump, the Interior issued 9 of 11 leases totaling 437,804 acres. President Biden paused all activities related to BLM’s Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program in January 2021 through Executive Order 13990 (Federal Register 2021). Trump recently reversed this by allowing oil drilling and development leases to continue. Trump believes that opening up the Coastal Plain will ‘unleash’ domestic energy and reverse years of more restrictive policies, including Biden’s pause on lease cancellation (White House 2025). Lease sales allow companies to bid for the right to explore and potentially drill an area, and the actual development of oil comes years later, after permits are acquired and infrastructure is built. For example, places that have never seen industrialization or been touched by humans, construction, infrastructure development, seismic testing, and pipeline construction will be introduced. Trump and the Interior argue this will strengthen energy security, support “local control,” and unlock “promising untapped energy resources.”

The Gwich’in Nation Steering Committee condemns the actions the Trump Administration took to open the entire Coastal Plain, claiming the plan is a threat to the Porcupine Caribou calving and nursery grounds there, and therefore to their entire way of life. The Gwich’in call the Coastal Plain of the Arctic Refuge, Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit, which means “the sacred place where life begins” in their language. The Porcupine Caribou are essential to the nutritional, cultural, and spiritual needs of the Gwich’in Nation, and they have been fighting to protect the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou herd for decades. Any disruption to these lands in the Arctic Refuge, according to the Gwich’in, would negatively affect their health and migration routes. Kristen Moreland, executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, stated that “this action by the Trump administration is a direct attack on the Gwich’in, who have for decades been a voice for the caribou and stood against the destruction of the Arctic Refuge. A leasing program that would open the entire Coastal Plain completely ignores the impacts that oil and gas development would have on the land, on wildlife, and on our communities,” (Gwich’in Steering Committee 2025).

Earthjustice, NRDC, and others call the Trump Administration’s decision to open up the entire Coastal Plain a “massive public lands attack” that auctions off treasured lands to fossil fuel companies. These groups have concerns about burning oil from ANWR, which would increase greenhouse gas emissions, and about backslides on U.S. climate commitments.

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy and other state economic officials have voiced support for expanding oil drilling in the state. In June, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Lee Zeldin, U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, and U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright outlined the impact President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) will have on unleashing energy and economic growth in Alaska. The state’s energy sector employs about 8% of all payrolls and generates nearly one-fifth of total business earnings, the fourth-highest share among states (Anchorage Daily News 2025). This legislation will protect approximately 14,000 full-time equivalent jobs over the next four years while creating thousands more. In an interview with the Anchorage Daily News, Administrator Zeldin and Secretaries Burgum and Wright stated that “With the passage of OBBB, Alaska will be liberated from the radical environmentalism that has kept its extraordinary resources locked away for far too long. It reverses the damage of the Biden administration by opening federal lands and waters to oil, gas, coal, geothermal and mineral leasing while rescinding every so-called ‘green’ corporate welfare subsidy from Democrats’ ‘Inflation Reduction Act.’” (EPA 2025) Republicans cast environmental opposition as “blocking progress” and harming working families in Alaska; they say technological advances can minimize environmental harm.

As Indigenous nations and environmental groups are expected to sue again arguing violations of NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, and treaty/Trust obligations, there is always a possibility that this expansion will be reversed. As a reminder, Biden’s Interior Department suspended and later canceled the original leases, citing legal and environmental flaws in the Trump-era review. Earlier this year, a federal judge in Alaska held that the Biden administration lacked authority to cancel the leases unilaterally, sending the issue back to Interior—and effectively clearing a path for the new Trump team to proceed.

“The repeal of the Biden-era Record of Decision for the Arctic Leasing Program, and the move to open over 1.56 million acres of public land for auction has the potential to cause irreparable damage to the Gwich’in way of life,” said Galen Gilbert, First Chief of the Arctic Village Council. As oil executives size up the Coastal Plain, and the first lease sale could come within months, the Gwich’in and many other lawyers and activists prepare for a long battle against the Trump Administration and over whether oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Range is in the name of climate and nature protection.

Hi, my name is Abby West, I’m from Westchester NY, my role at HM is Associate Reporter-U.S. Policy. My majors are PPL and History, I am a sophomore, and I am on the pre-law track. I plan on going to law school after graduating early and pursuing an MBA. My research interests are in U.S. politics and policy, international affairs, and human rights. For my extracurriculars, you can find me on E-board for RENA Fashion Magazine and Binghamton Upcycle Project, as well as a part of Moot Court, Pipe Dream, the Food Co-Op, and working at Dick’s Sporting Goods. I also have my own political blog called ImpactInTen!

References

a52d663b_admin. 2025. “Gwich’in Nation Condemns Actions by the Trump Administration to Open Entire Coastal Plain of the Arctic Refuge to Oil and Gas Development.” Gwich’in Steering Committee. https://gwichinsteering.org/gwichin-condemn-arctic-refuge-drilling/ (Accessed November 26, 2025).

“Alaska (U.S. National Park Service).” https://www.nps.gov/locations/alaska/index.htm (Accessed November 25, 2025).

“Arctic National Wildlife Refuge — Oil and Gas Development – Environmental and Energy Law Program.” https://eelp.law.harvard.edu/tracker/arctic-national-wildlife-refuge-oil-and-gas-development/ (Accessed November 25, 2025).

“Interior Takes Bold Steps to Expand Energy, Local Control and Land Access in Alaska | U.S. Department of the Interior.” 2025. https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-takes-bold-steps-expand-energy-local-control-and-land-access-alaska (Accessed November 24, 2025).

“Opinion: Alaska’s energy renaissance awaits, and the One Big Beautiful Bill is the key to unlocking it.” Anchorage Daily News. https://www.adn.com/opinions/2025/06/08/opinion-alaskas-energy-renaissance-awaits-and-the-one-big-beautiful-bill-is-the-key-to-unlocking-it/ (Accessed November 26, 2025).

“Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science To Tackle the Climate Crisis.” 2021. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/25/2021-01765/protecting-public-health-and-the-environment-and-restoring-science-to-tackle-the-climate-crisis (Accessed November 26, 2025).

“Trump Administration Opens the Entire Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to Oil and Gas Leasing.” Earthjustice. https://earthjustice.org/press/2025/trump-administration-opens-the-entire-coastal-plain-of-the-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge-to-oil-and-gas-leasing (Accessed November 24, 2025).

“Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.” 2025. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-alaskas-extraordinary-resource-potential/ (Accessed November 26, 2025).

US EPA, OA. 2025. “ICYMI: Administrator Zeldin in Anchorage Daily News: ‘Alaska’s energy renaissance awaits, and the One Big Beautiful Bill is our key to unlocking it.’” https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/icymi-administrator-zeldin-anchorage-daily-news-alaskas-energy-renaissance-awaits-0 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

US EPA, OAR. 2024. “Drivers of Climate Change in the Arctic.” https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/drivers-climate-change-arctic (Accessed November 25, 2025).

-

The Story of Populist Rhetoric and Image in the Age of Information

By Morgan Reed-Davis, Political Theory

“Eat the Rich.” “Power to the People.” “Make America Great Again.” These populist slogans pop up everywhere, from graffiti under an overpass to TikTok “For You” pages. The basic populist message—“the people” versus “the elites”—isn’t new. It was used by American revolutionaries in the 1700s, rebellious farmers in the late 19th century, and even anti-communist politicians in the 1950s (Gillon 2025). But over the past half-century, populist rhetoric has dramatically increased on both the right and left.

So what changed? While there’s no definitive answer, there are plenty of questions worth exploring. This article tackles four of them: What is populism? What does populism look like in 2025? What caused its rise, and how is it related to the phones in our back pocket?

What is populism?

Unlike other political ideologies, populism has a fluid definition. Its rhetoric splits society into the “people” and the exploitative “elites” (Pappas 2019).The message is fundamentally anti-establishment, and revolves around concerns of social and economic change, government corruption, and uplifting the voice of the “common people.” What makes the definition fluid is that these factors change depending on who defines “the people” and “the elites.”

On the left, the “elites” are typically billionaires, corporate giants, and hard-right conservatives (Ruth-Lovell 2025). Left-wing populists tend to push progressive policies like taxing the rich and affordable healthcare (Macedo and Mansbridge 2019). The “people” are often the working-class, minorities, and other leftists. On the right, “the elites” are usually framed as government insiders, the liberal media, and cultural outsiders like immigrants (Nadeem 2021). Right-wing populists champion economic policies such as deregulation and tariffs, as well as social issues related to national identity and traditional values. In this case, the “people” are often conservative blue-collar workers, most of whom are nostalgic for the traditionally conservative America of the past.

It’s important to note that political theorists often use the term “populist” pejoratively. A historic ultra-nationalist flavor of populism that has made the term synonymous with authoritarians and double-dealing demagogues. However, populism in the modern day, at least, in America, challenges that definition.

Case study: Zohran Mamdani and Donald Trump

Let’s start with Zohran Mamdani. The 34-year-old former assemblyman from Queens shocked the nation when he won the NYC mayoral race in November (NBC 2025). Mamdani identifies as a democratic socialist, setting him apart from the democrat-led establishment. Mamdani led a successful grassroots campaign, personally walking with supporters on the streets of New York, eating with locals, visiting gay bars, and connecting with a diversity of NYC communities (Cuevas 2025). His message—that NYC had become unaffordable and he could fix it—resonated with New Yorkers who’d been struggling to afford the city’s skyrocketing cost of living (Mamdani 2025). Mamdani’s promises include rent freezes for rent-stabilized tenants, new affordable homes, universal childcare, and a faster public transit system (McKurdy 2025).

On the right-wing side of populism is President Donald Trump. His first significant political swing was his 2016 presidential run, and he casted himself as no-nonsense outsider with a business expertise that could fix the American economy (Duignan 2025). Worried about China, immigration, and loss of American industry, Trump pushed economic and social policies like tax cuts, deportations, and aggressive tariffs. His 2024 campaign repeated this formula, focusing on deportations, tariffs, and undoing the damage he said the previous administration caused (Esomonu 2025). In both instances, he gave working- and middle-class conservatives a romantic vision: he could “Make America Great Again” (Volle 2025). Trump and Mamdani may land on opposite ends of the political spectrum, but they share an outsider status, charisma, and an anti-establishment message that makes them populist.

What caused the increase in populist rhetoric?

There are plenty of theories. Neoliberalism’s effects on labor markets and income inequality, the loss of national identity, and even the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 are all considered by political theorists as possible starting points (Cox 2018). However, in light of today’s social-media-savvy politicians, one theory seems the most plausible. The theory posits that politics, entertainment, and information began to blend in the age of television. Populism– which requires a showmanship almost adjacent to entertainment – not only survived but thrived in this new environment.

Television became the dominant medium in the 1960s, forcing politicians to adapt to its emphasis on convenience and performance. Television is a medium for entertainment that centers around an oversimplified, dramatized, emotion-driven “logic of mass media” (Gianpietro 2008). As the “logic of mass media” became more widespread, more of the public began measuring a politician by their image and simplistic message rather than their merit. What that means is that politicians and political debate needed to have some sort of entertainment value (i.e., showmanship) to “survive” on television, which had become the ultimate medium to get the attention of potential voters.

For example, take the first televised debate between Nixon and Kennedy in 1960. Appealing to an audience accustomed to sitcoms and hour-long newscasts, the Nixon-Kennedy debate was scheduled for only an hour and interrupted by advertisements (Library of Congress). By comparison, the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 were three hours long with no intermission. Kennedy was composed and well-spoken; Nixon, on the other hand, spent the hour looking shifty and out of place. Nixon himself pointed out his fatal mistake: “I paid too much attention to what I was going to say and too little to what I looked” (Time 1968). In the age of television, politicians were incentivized to take on a specific role: a man of style, a celebrity of sorts. This “role” became a reality. 1981, Ronald Reagan, a former Hollywood star, became the first celebrity president and the prototype for modern American populism (Lundskow 1994).

The fusion of politics and entertainment continued as information became more abundant in the 1980s and 90s. Before the 1990s, the big three media companies (NBC, ABC, CBS) controlled the television industry (Allen, Stevens, Thompson 2025). However, the 90s saw the multiplication of news channels, the dawn of the 24-hour news cycle, the rise of multiple TV households, and the rise of the computer (Blumler and Kavanagh 1999). Americans had far more choices in information and entertainment, meaning that media organizations had adapted to the public’s expectations to keep their attention. News broadcasters made efforts to make politics palatable, while politicians began acting more personable on screen. Along with this, new stations that wished to inform and persuade had to compete with “infotainment” (i.e., cooking shows, talk shows, and magazines) designed to merge information with the fiction of TV personalities (Diehl 2024). Competing with the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, politicians had to sell their image—their “brand”—just as much as they had to sell their message.

As a result, presidential campaign strategies leaned heavily on marketability and media appearances. For example, news coverage of an alleged 12-year affair nearly ended Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. After an interview on 60 Minutes, his popularity rebounded, and he resumed his campaign under the slogan “It’s the economy, stupid” and the self-given nickname “comeback kid” (Levy 2025). While the media has influenced politics in the past, in this digital age, it can immediately destroy and revitalize a career; politicians who could charm some of the public and the press, such as Bill Clinton, had a better chance of being the latter.

In the 2000s to 2020s, the boundaries between politics, entertainment, and information continued to blur as social media changed people’s perceptions of information, creation, and attention. In the early 2000s, information proliferated at an unprecedented rate, with content jumping from news channels to Wikipedia articles to blog posts. The invention of the iPhone in 2007 made a surplus of information available to users at any time and place (Britannica 2025). As for the creation of political commentary, journalists weren’t necessarily intermediaries anymore. With social media, users could be both producers and consumers of political discourse; someone could skim a CNN article, latch onto a detail, and publish it for the world (or their 15 followers) to see.

In the 2020s, fifteen-second short-form content like TikToks and Instagram reels fracture and decontextualize political information. It’s not uncommon to scroll through a For You page, stumble on footage of a political violence, and then, not even 15 seconds later, see A.I.-generated brainrot. In the age of social media, millions of people (i.e., influencers, journalists, celebrities) and millions of pieces of information (i.e., articles, TikToks, ebooks) compete for people’s attention. There are so many choices and clamoring voices, one is dizzied by the thought of having to decide what information is worth paying attention to. In a way, attention is a form of currency. It’s easy to make a bad investment if one can’t predict the rate of return.

At face value, populism is a safe bet. Its rhetoric is palatable and attractive, and doesn’t require any mental gymnastics to understand. Populists provide a checklist of promising policies, have the flair of a celebrity, and often share the public’s disdain for the stiff, over-media-prepped politicians of the current establishment. Not to mention, social-media-savvy populists like Mamdani and Trump (or at least Trump in his first term) connect to their supporters directly and immediately, almost becoming one of “the people” by sharing a digital space. One doesn’t need to exert too much time or energy deciding which politicians are worth their attention; populists catch their attention naturally.

Perhaps, this is what makes populism so alarming. The “people versus the elites” rhetoric appeals to emotions—to anxieties of the future, frustrations with the present, love for the past. Populists may be well-intentioned or they may be deceptive, but either way emotion-driven rhetoric and a celebrity image define their campaigns. Emotion may be important for political dialogue, but logic and attention are essential. And in an age where logic and attention is hard to come by, and political dialogues are becoming increasingly contentious, populists are stealing both.

Morgan Reed-Davis is a junior from Carver, MA double-majoring in English Literature & Rhetoric and Philosophy, Politics, and Law (PPL). After graduation, she plans to attend law school and one day fulfill her lifelong dream of having a pet rabbit. As a political theory reporter, Morgan is deeply interested in researching political rhetoric, the attention economy, and LGBTQ theory, among other things. In her free time, she enjoys crocheting/knitting, writing, reading, and hobby jogging.

References

Allen, Steve, Thompson, Robert J.. “Television in the United States”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Jul. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/art/television-in-the-United-States. Accessed 24 November 2025.

Blumler and Kavanagh. The Third Age of Political Communication: Influences and Features: Political Communication: Vol 16, No 3, 1999, www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/105846099198596.

Britannica Editors. “iPhone”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Nov. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/technology/iPhone. Accessed 24 November 2025.

Britannica Editors. “Ronald Reagan”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 Nov. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ronald-Reagan. Accessed 23 November 2025.

Cox, Michael. Understanding the Global Rise of Populism, LSE IDEAS, Feb. 2018, http://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/updates/LSE-IDEAS-Understanding-Global-Rise-of-Populism.pdf.

Cuevas, Eduardo. “How Zohran Mamdani Won NYC: Be Everywhere. Talk to Everyone. Focus on Affordability.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2025/11/07/how-zohran-mamdani-won-nyc-mayor/86580734007/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

Diehl, Paula, ‘Populism, Celebrity Politics, and Politainment’, in Giuseppe Ballacci, and Rob Goodman (eds), Populism, Demagoguery, and Rhetoric in Historical Perspective (New York, 2024; online edn, Oxford Academic, 24 Oct. 2024), https://doi-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/10.1093/oso/9780197650974.003.0013, accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

Duignan, Brian. “Donald Trump”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Nov. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Donald-Trump. Accessed 24 November 2025.

Esomonu, Eunice, et al. “Tracking Trump’s Presidential Promises.” AP News, AP News, 19 May 2025, apnews.com/projects/trump-campaign-promise-tracker/.

Gillon, Stephen. “Why Populism in America Is a Double-Edged Sword.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, 28 May 2025, http://www.history.com/articles/why-populism-in-america-is-a-double-edged-sword.

Gianpietro Mazzoleni, “Populism and the Media,” in Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, ed. Daniele Albertazzi and Duncan McDonnell (Hampshire, UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008

Levy, Michael. “United States presidential election of 1992”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 Oct. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1992. Accessed 24 November 2025.

Library of Congress. “Today in History – October 21 | Library of Congress.” Congress.Gov, http://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/october-21/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

Lundskow, George. “Smiles, Styles, and Profiles: Claim and Acclaim of Ronald Reagan as Charismatic Leader.” Social Thought & Research, vol. 21, no. 1/2, 1998, pp. 185–214. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23250037. Accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

Mamdani, Zohran. “Zohran Kwame Mamdani on Instagram: ‘Every Politician Says New York Is the Greatest City in the World. but What Good Is That If No One Can Afford to Live Here? I’m Running for Mayor to Lower the Cost of Living for Working Class New Yorkers. Join the Fight. Zohranfornyc.Com/Donate.’” Instagram, http://www.instagram.com/reel/DDS6ZafOnrU/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA. Accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

Macedo, Stephen, and Jane Mansbridge. “Populism and Democratic Theory | Annual Reviews.” Populism and Democratic Theory, 2019, http://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042843.

McKurdy, Kara. “Zohran Mamdani for New York City.” Platform, 2024, http://www.zohranfornyc.com/platform.

Nadeem, Reem. “5. Populist Right.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 9 Nov. 2021, http://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/11/09/populist-right/.

NBCUniversal Media. “NYC Mayor Election 2025 Results: Zohran Mamdani Wins.” NBCNews.Com, NBCUniversal News Group, 20 Nov. 2025, http://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2025-elections/new-york-city-mayor-results.

“Nixon’s Hard-Won Chance to Lead.” Time, Time, 15 Nov. 1968, time.com/archive/6657071/nixons-hard-won-chance-to-lead/.

Pappas, Takis S., ‘What Causes Populism?’, Populism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 May 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198837886.003.0003, accessed 23 Nov. 2025.

Ruth-Lovell SP, Wiesehomeier N. Populism in Power and Different Models of Democracy. PS: Political Science & Politics. 2025;58(1):87-90. doi:10.1017/S104909652400043X

Volle, Adam. “MAGA movement”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Oct. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/MAGA-movement. Accessed 24 November 2025.

-

The Electoral College and Antimajoritarianism

By Chase Quinn, Elections

The United States prides itself on democratic and egalitarian values. Despite this, we choose to elect our executive by means of an Electoral College, which due to its nature, sometimes produces antimajoritarian election outcomes. These results go against the wishes of a majority of voters. This is easiest explained by looking at the popular vote in our presidential elections. Since the founding of the country, anti-majoritarian results have happened a total of five times in our presidential elections. The two most recent were in 2000 and 2016. In 2000, Al Gore lost the election to Geroge W. Bush despite winning the popular vote by over 500,000 votes, while Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump in 2016 despite winning 3 million more votes than him (American Presidency Project 2024). Both are cases in which candidates won the presidency despite winning less votes than their opponents. The other three antimajoritarian elections were in 1824, 1876, and 1888.

Margins for the 1984-2020 presidential elections are shown in Figure 1, with graph color corresponding to the winning party for that year’s election. Margins represent the amount of votes that a candidate won or lost the popular vote by. A negative margin represents candidates that won the election despite losing the popular vote.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

In a comparative sense, the electoral college is an institution very specific to the United States. No other country in the world uses a system like this to elect their executive office, instead using direct elections (Sacher 2024). Contrary to popular belief, in the United States we do not directly elect our president, the electoral college does. Proponents of reform argue that utilizing a direct election method would be more democratic, as it would utilize a “one person one vote” framework where each individual vote is truly considered equal and not affected by the state where one lives. To illustrate this, we can look at the proportion of electoral college votes to state populations.

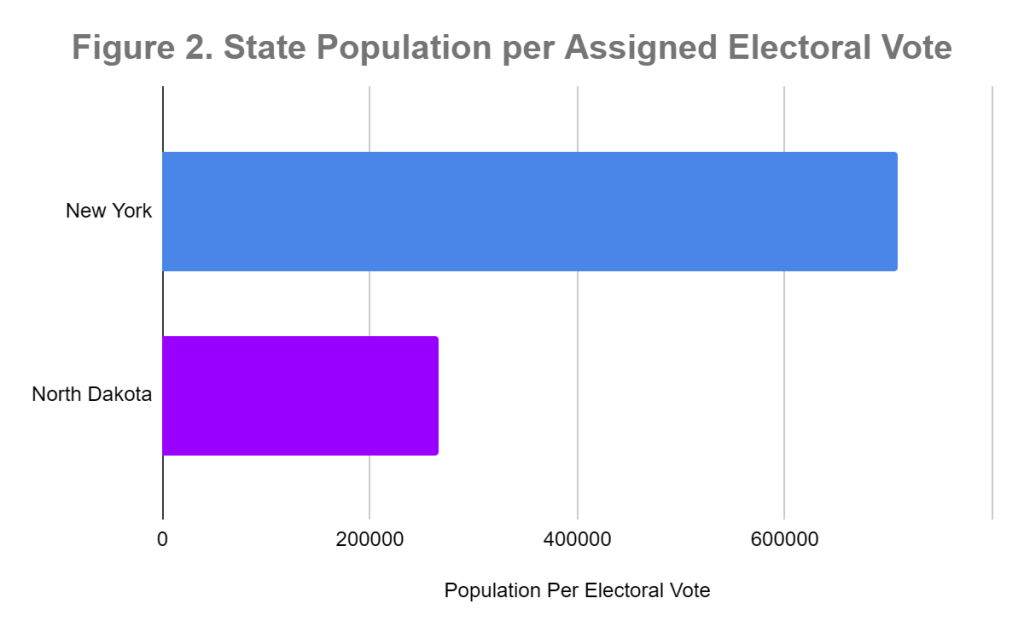

Advocates of electoral college reform point out that the weight of individual votes differs between states and disproportionately benefits states with low populations. Take for example North Dakota, the fourth least populous state, compared with New York, the fourth most populous state. North Dakota has a total of 3 electoral college votes, while New York has 28.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.census.gov/popclock/

A simple calculation of the proportion of population to electoral votes in each state shows some discrepancies, shown in Figure 2. Despite the drastic difference in populations, individual votes have much less weight in New York than they do in North Dakota. For every electoral college vote assigned to North Dakota, there is a population of 265,523 individual voters, more than half of the amount it takes in New York of 709,445 individual voters per electoral vote assigned. Individual votes in more populous states are given less weight than those in less populous states, despite the fact that populous states make up a greater proportion of overall population and thus represent more people. For reference, comparing state populations to the total population of the United States, New York makes up 5.7% of total population while North Dakota makes up only 0.23%, showing that New York has 25x more people than North Dakota. Electoral college votes are assigned to states based on proportion to population, but the minimum number of votes assigned to each state is three. If this minimum were to be removed, sparsely populated states like North Dakota would have less than three electoral votes as they represent proportionally much less people than populous states.

Nullified Votes and Safe States

Another criticism of the electoral college is that it routinely renders large proportions of the country’s vote to be null and void. If you are a Republican living in a heavily-leaning Democratic state, for example, your vote in the Presidential election is essentially meaningless. Every election your vote is cast, but it makes no dent on the overwhelming state majority that votes Democrat, giving all of your state’s electoral votes to the opposing party and rendering your vote as having essentially no effect on the race.

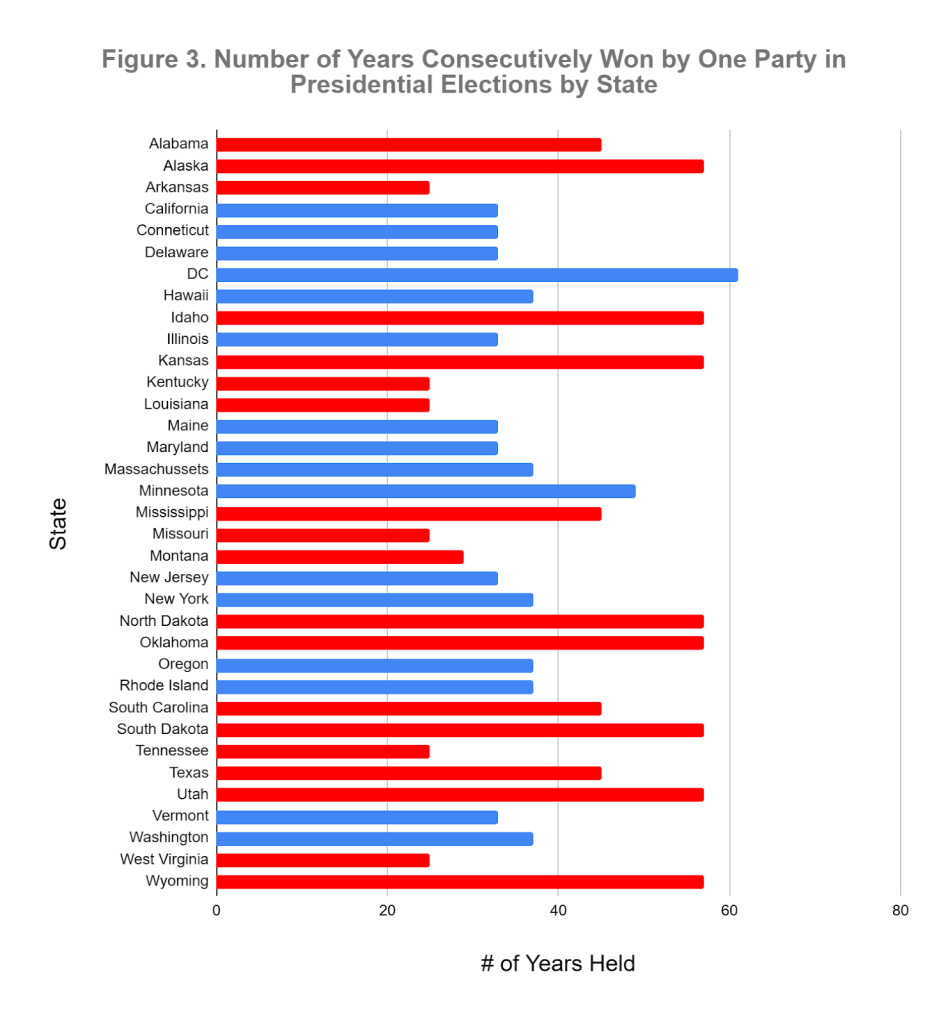

This is an especially prevalent issue in political “safe” states. These are states in which political beliefs stay relatively stable, and in which the same party has stayed dominant for an extended amount of time (in this case for 20 years or more). Alaska is a great example of this. For the past 15 presidential elections Alaska has voted Republican, marking a 57 year long period where the majority of voters have not changed their general political stances. If you are a Democrat or align with any other party in Alaska, however, your vote has been considered meaningless for the last 57 years, as a vote that does not produce any electoral college votes is useless in the overall election. Figure 3 shows the number of years that different states have been consecutively under one party control in presidential elections. This data only includes politically safe states and excludes swing states. Each state is color coded by the party in control. Note that despite not being one of the 50 states, DC is included as it is given three electoral votes and treated as its own electoral entity under the 23rd Amendment.

Created by Chase Quinn using data provided by https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

This is an issue that ascends partisanship, with nullified votes happening to both Democrats and Republicans as well as third parties across the country on every presidential election. The electoral college thus puts a heavier emphasis on swing states, which have very close margins and are easier to flip from party to party. As such, swing states are high priority targets for presidential campaigns, as flipping a single state could mean victory. Political competition has shifted to swing states so much that politically safe states have been observed to have lower voter turnout than swing states. During the 2016 election, 80% of states labeled “battleground states” by NPR reported higher voter turnout than the national average (Kurtzleben 2016).

Voters in noncompetitive states face a dilemma. For example, say you are an Alaskan Republican voting in the 2028 presidential election. Alaska has voted Republican for 57 straight years and is very likely to vote Republican again. You’re satisfied with the results, but why bother going to the polls if you know that your party is going to win anyway? In the same vein, if you are a Democrat or third party voter in Alaska, it seems hopeless to cast a vote in an election that seems to be lost from the get go. On either side of the aisle voters are discouraged from casting their votes, leading to less political competition and less representation.

Reform

Examining issues like this then begs the question, why do we still have the electoral college? In widespread national studies, polling has consistently shown that a majority of voters would prefer to see the electoral college removed and replaced by a national system of voting, similar to how other countries do it. A 1981 national poll found that 75% of Americans favored the abolition of the Electoral College (West 2020). Over the years, however, sentiments have been changing, with new trends emerging among partisans. Despite this, there is still a majority of support in favor of doing away with the Electoral College. A more recent Gallup survey done during the 2000 Presidential Election found that 73% of Democratic respondents supported abolition, while only 46% of Republicans did as well (West 2020).

Abolition of the Electoral College faces two major issues: conflicting interests, and unanimous consensus. The main way to realistically reform our Presidential voting system would be to pass a constitutional amendment, which requires a very strong consensus of at least two-thirds of both chambers of Congress. While it is not entirely unrealistic, it is definitely difficult. Even if a reform bill manages to pass this threshold, it must also be ratified by at least three quarters of states to be considered valid. Past measures to do away with the electoral college have come close to success, but ultimately failed, such as an attempt done in 1969-1970 (Silva 2013).

Then there’s also competing political interests. Both dominant parties in the United States benefit from the electoral college to some degree. In politically safe states, the electoral college provides an easy way to gain votes while nullifying those of the opponents. Candidates can rely on safe states for large amounts of their electoral votes and focus on fewer crucial swing states to try and win the election. Remember from Figure 3, a majority of states are considered politically safe and political attitudes typically change little from election to election. The electoral college also makes the political system less competitive considering the possible impact of third parties on elections. It’s extremely difficult for third parties to gain any sort of traction in a national presidential election because they face such high thresholds to secure electoral votes. The last time a third party candidate won any states was in 1968, when George Wallace won 46 electoral votes running under the American Independent Party, but even he was still far from victory (The American Presidency Project n.d). Democrats and Republicans both benefit from this effect, as it keeps competition from additional parties essentially nonexistent.

As a result of these factors, there’s conflicting motivations for current party politicians to advocate for reform. And with politics becoming increasingly polarized between Democrats and Republicans, they probably have other things on their minds besides abolishing the electoral college.

Chase Quinn is a senior at Binghamton University serving as the elections reporter. He studied journalism at Hunter College for two years before transferring to Binghamton to pursue a bachelors in Political Science and Master’s in Public Administration. He was born and raised in the town of Pine Plains, New York. Post-college he plans to conduct research on policy and law and aims to work in the public sector. In his free time, Chase likes to read, spend time outdoors, create art, and make jewelry.

References

Woolley, J. T., & Peters, G. (2024, November 6). Presidential election margin of victory. Presidential Election Margin of Victory | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/presidential-election-mandates

Woolley, J. T., & Peters, G. (n.d.). 1968: The American presidency project. 1968 | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections/1968

Sacher, J. M. (2024, September 16). Why does the U.S. still have an electoral college?. University of Central Florida News. https://www.ucf.edu/news/why-does-the-u-s-still-have-an-electoral-college/

Silva, R. C. (2013, September 2). The Lodge-Gossett resolution: A critical analysis: American political science review. Cambridge Core. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/abs/lodgegossett-resolution-a-critical-analysis/98DF1DCFC665D06C399A6D64C1DBBDB6

Kurtzleben, D. (2016, November 26). Charts: Is the electoral college dragging down voter turnout in your state?. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2016/11/26/503170280/charts-is-the-electoral-college-dragging-down-voter-turnout-in-your-state

West, D. M. (2020). It’s time to abolish the Electoral College Policy . Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/big-ideas_west_electoral-college.pdf

Population clock. United States Census Bureau . (n.d.). https://www.census.gov/popclock/

Election results and voting information. Federal Elections Commission . (n.d.). https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-results-and-voting-information/

-

A Longstanding Program in Danger: The History of the US SNAP Program

By Jadyn Schoenberg, Political History

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the United States’ largest program aimed at combating hunger. However, it is currently under attack by the Trump administration, and millions of Americans are at risk of their welfare benefits being cut. The government is funding 65% of the SNAP program benefits, claiming that it is all they can afford. In early November 2025, John J. McConnell Jr., a Rhode Island federal judge demanded the government pay 100% of what SNAP recipients are entitled to. The federal government agreed, but then rescinded their promise after states had dealt out the full benefits to their respective recipients. Rhode Island Governor Dan Mckee stated about Trump retracting his claims, “he intentionally created chaos for states across the country playing games with people’s ability to feed their families, weaponizing hunger, and gaslighting the American people. It’s inhumane” (Smith 2025). Trump’s attempts to weaken the SNAP program reflects the most recent transformation to an ever-changing program that has been remodeled by government legislation throughout history.

The History of SNAP Benefits

The first food stamp program in the U.S. was introduced during the Great Depression. In the four year duration of the program, 20 million Americans facing food insecurity were helped, but the program was designed to be temporary and ceased in 1943, when the unemployment epidemic in the U.S. was rectified. A food stamp program would not return until the Pilot Food Stamp Program was introduced in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy. The early food stamp programs were characterized by a purchase requirement, in which participants had to spend their own money on stamps to acquire food at a discounted price. A major expansion of the program occurred following Lyndon Johnson’s passage of the Food Stamp Act in 1964 which outlawed discrimination in food stamp distribution, removed limits on the kind of items people could purchase with food stamps, and made the program a permanent fixture in American society. (A Short History of SNAP 2025). This legislation came in the midst of Johnson’s Great Society policies aimed at combating poverty in the U.S.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the program continued to grow from a recipient standpoint, and also in terms of the quantity of states providing these benefits. The rapid expansion of the program led to concerns over the price of providing food stamps to so many people, and it facilitated the passage of several pieces of legislation such as the Food Stamp Act Amendment of 1970, which limited the quantity of food people could purchase with subsidies to what constituted a “nutritionally adequate diet.” In addition, to buy food stamps, people had to prove that they were taking initiative to make their own money with proof of employment and spending at least thirty percent of their income on food before the government stepped in to provide assistance (A Short History of SNAP 2025).

Despite the limitations the Food Stamp Act Amendment implemented, the program would continue to grow with the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973, which expanded the program to all states and facilitated the program’s nationalization by 1974. The program was made more accessible with the passing of the Food and Agriculture Act of 1977, which eliminated the purchase requirement, meaning people no longer had to pay for food stamps. Restrictions on food stamp collection were further mitigated when the Food Stamp Act of 1985 downgraded the requirements for enrolling in benefits from having a job to solely participating in the Employment and Training Program, which was legally required in all states (A Short History of SNAP 2025).

Access to food stamps was facilitated by the nationwide implementation of Electronic Benefit Programs in 2002 after the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. The EBT programs effectively removed physical food stamps, allowing people to collect their benefits via swiping a government-issued card (A Short History of SNAP 2025).

Food welfare assistance followed a cyclic pattern of expanding and then contracting. Each time the program expanded, laws were passed that restricted the program, and when the program reached lulls, legislation was implemented to increase participation. An example of this is with the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 and the Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002. For example, upon the program expanding in the 1980s, immigrants were barred from receiving the benefits; however, six years later this decision was reversed when immigrants who, after five years of living in the U.S., were permitted to collect food stamps. This reversal came during a period of participation decline in the 1990s (A Short History of SNAP 2025).

In 2008, The Food, Conservation and Energy Act substantially increased funding to these programs by over a billion dollars each year. Per this Act, the program was officially titled the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP). Following the 2008 recession, the program experienced continuous growth (A Short History of SNAP 2025). However, the program is currently in danger of a serious contraction; but this should not come as a surprise to the American populace, as Republican administrations generally tend to target welfare programs.

Democrats and Republicans on Food Stamps

The political right and left generally have different perspectives regarding the distribution of welfare benefits. Republicans intend to minimize government funding for welfare programs, such as SNAP, and want to decrease the money spent on these programs by decreasing the amount of recipients of these benefits. Republicans want to add more work requirements, making the benefits less attainable for the unemployed. On the other hand, Democrats are proponents of expanding welfare programs, simplifying the process of joining the program and collecting its benefits, and are against tightening the work requirements (Farley 2025). The most recent government shutdown was the result of disagreements between Congressional Democrats and Republicans over government funding for Obamacare subsidies. Due to the shutdown, Congress failed to renew funding for SNAP assistance, leaving millions with the risk of food insecurity.

Although expansions and cuts of welfare programs have occurred during Democrat and Republican administrations, the most notable growths of food-based welfare occur during Democratic presidencies and the most notable cuts during Republican leadership. For example, the food stamp program became permanent in American society under Democrat President Lyndon B. Johnson, and the purchase requirement for food stamps was eliminated, which ultimately made food stamps easier to obtain in 1977 under Democrat President Jimmy Carter. In contrast, the legislation that restricted food stamp purchases to only the items that constituted a “nutritionally adequate diet” occurred under the Nixon administration. Lastly, the Food, Conservation and Energy Act of 2008 that sought to increase funding for these programs was initially vetoed by Republican President George W. Bush, and it only passed because the veto was overridden by a Democrat-dominated Congress.

The recent threats to welfare programs place the food security of many Americans in jeopardy, but they are evidence of a longstanding pattern in American society of Republican leaders reducing government spending on welfare benefits.

Jadyn Schoenberg is a sophomore majoring in Philosophy, Politics and Law from Commack, NY. She is an Associate Political History Reporter, who plans to attend law school in the future. Her political interests include democratic backsliding, international law and legal history. Aside from writing, she enjoys playing ultimate frisbee and spending time outdoors.

References

“A Short History of SNAP.” Food and Nutrition Service U.S. Department of Agriculture, August 29, 2025. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/history.

Farley, Robert. “Democrats and Republicans Clash Over SNAP Contingency Funds.” FactCheck.org, October 31, 2025. https://www.factcheck.org/2025/10/democrats-and-republicans-clash-over-snap-contingency-funds/.Smith, Tovia, Chandelis Duster, and Jennifer Ludden. “Trump Administration Again Asks Supreme Court Intervene on Order for Full SNAP Benefits.” NPR, November 10, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/11/09/nx-s1-5603417/full-snap-benefits-trump-states-order.

-

Evangelical Christianity and American State Ideology: A Historical Review

By Travis Rayome, Political History

When the 13 colonies were established throughout the 16th-18th centuries, the myriad Christian denominations that found themselves in the New World began integrating religious practices into the laws of their respective colonies. Some, like the Virginia Colony, integrated themselves into the Old World’s theocratic structures; the first Virginia House of Burgesses meeting in 1619 established compulsory attendance of the Church of England (also known as the Anglican Church) and passed laws mandating that all Virginians do “God’s service” in accordance with Anglican teachings (Marcus 2022). However, other colonies, primarily the Pilgrims and Puritans of New England, came to North America to distance themselves from Europe’s religious hegemonies (in particular, Catholicism and Anglicanism) and established their societies on unique religious structures. No matter how they related to existing Christian institutions, though, many of the 13 colonies were explicitly theocratic. Religion was emphasized and participation was often enforced by colonial governments as a binding force between colonists coming from different localities and cultures in Europe, something to enforce social cohesion and moral order (Marcus 2022).