By Joseph Brugellis

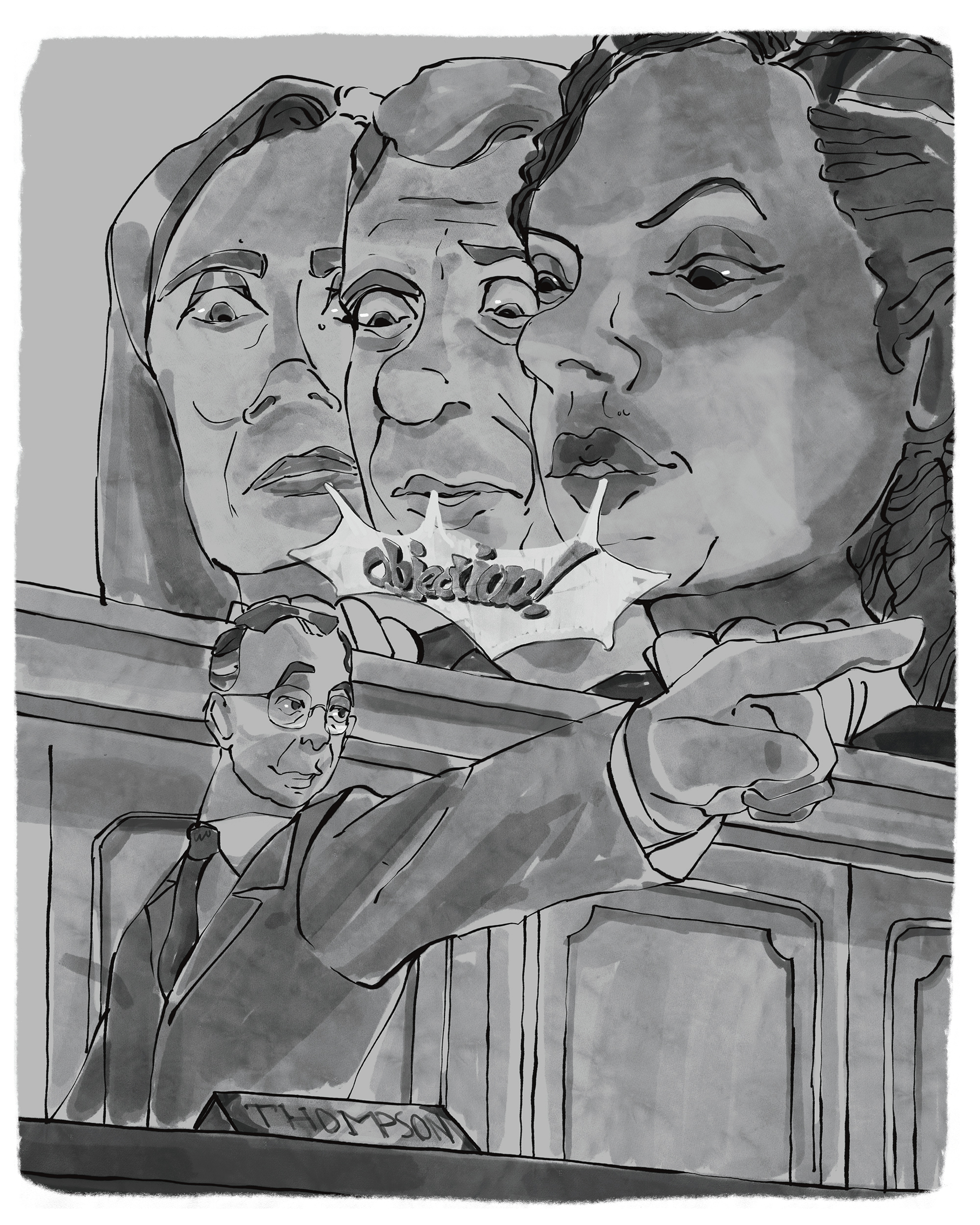

Art by Rhea Da Costa, Resident Artist

Read this article and more in our 2023 winter edition, on campus now!

When Americans go to the polls to elect their next congressperson, they are often unaware of the critical role that state legislatures play in administering federal elections. The Elections Clause of the United States Constitution gives state legislatures the power to govern how federal elections are conducted (US Const. art. I, §4). It has long been understood that this lawmaking authority is not unlimited; state courts reserve the right to ensure that the federal election laws and procedures approved by the legislature “comply with [the] state constitution” (Herenstein and Wolf 2022). As an example, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in recent years has held that partisan gerrymandering by the state legislature in the congressional redistricting process violates the state constitution (Chung 2018).

This widely held legal precedent is now under threat. In November 2021, the Republican-led North Carolina General Assembly passed a new congressional redistricting map. Several voting rights activists filed a lawsuit contending that this new map was a partisan gerrymander that violated several provisions of the state constitution. Three judges on the North Carolina Superior Court (a trial court) initially ruled against the activists and declined to block the redistricting map. The state Supreme Court, however, agreed with the voting rights activists, and, on February 4, 2022, directed the Assembly to craft a remedial map to be submitted to the trial court. Simultaneously, the trial court appointed three special masters on February 16 to draw their own proposed redistricting map. One week later, the trial court rejected the congressional map proposed by the Assembly, instead adopting the map drafted by the special masters. The Assembly appealed this decision to the US Supreme Court (“Brief for Petitioners” 2022).

On June 30, 2022, the US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in Moore v. Harper (“Order List” 2022), a case which could restrict the ability of state constitutions and courts to place limits on the power of legislatures to alter the federal elections process. The heart of this case concerns whether the Supreme Court should adopt a version of the so-called “independent state legislature” (ISL) doctrine, which asserts that state legislatures retain “broad power to regulate federal elections” (Howe 2022) without being subject to limits imposed by the state constitution and courts.

At stake? Democracy itself—a broad adoption of the ISL doctrine could result in rogue legislatures stripping previously-guaranteed voting rights protections from the state constitution with no ability for state courts to protect these rights

(“Transcript” 2022).

The ISL doctrine is of relatively recent vintage, first appearing more than 20 years ago in Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s concurrence in Bush v. Gore (2000) (Herenstein and Wolf 2022). After Al Gore formally contested the certification of Florida’s election results in the 2000 presidential election, the Florida Supreme Court created a novel system for a statewide voter recount. George Bush appealed to the US Supreme Court, which ruled 7-2 that the Florida Supreme Court’s recount scheme violated the 14th Amendment (“Bush v. Gore”). Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion where he also expressed the view that the Florida Supreme Court’s scheme violated the Presidential Elector Clause because only the “state legislature” can make the rules governing how presidential electors are to be chosen (V. Amar and A. Amar 2022). While advocating for the general supremacy of the legislature to govern how the electoral process operates, Chief Justice Rehnquist crucially “acknowledge[d] that state courts” play a key role in ensuring that state legislative action comports with the state constitution (“Transcript” 2022).

Proponents of the ISL doctrine claim that their position is supported by the Constitution (Brief for Petitioners 2022). The text of the Elections Clause states that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof…” (US Const. art. I, §4). The Constitution also contains the Presidential Elector Clause, which provides that the state legislature be given the power to appoint electors during a presidential election (US Const. art. II, §1). The ISL doctrine asserts that the Constitution’s usage of the term ‘legislature’—the state organ tasked with making and amending laws—rather than “the State as a whole” implies that other state entities (e.g. state courts) cannot interfere substantively in the legislature’s election law endeavors (“Brief for Petitioners” 2022). Unlike the version of the ISL doctrine embraced in the Rehnquist concurrence, the petitioners in Moore v. Harper go further and argue that state courts have no power to place substantive limits upon what the legislature may do (“Transcript” 2022).

Those opposed to the adoption of the ISL doctrine note how centuries of historical practice demonstrate that state legislatures could not ignore the state constitution when passing laws governing federal elections. Immediately after the Constitution was ratified in 1787, many states amended their respective constitutions to enact rules regarding federal election procedures. Delaware’s 1792 constitution, for example, contained a provision requiring that federal elections be conducted “‘by ballot’ rather than voice vote” (“Brief of Amici Curiae” 2022). By 1802, states like Vermont, Tennessee, and Ohio all had constitutional provisions mandating that federal elections be free and open to all (“Brief of Amici Curiae” 2022). As the 19th century progressed, state constitutions began to be more explicit in regulating the administration of federal elections. The constitutions of Indiana, Missouri, Mississippi, and Michigan, for example, set out a specific time for federal elections to be conducted (“Brief of Amici Curiae” 2022). According to those opposed to the adoption of the ISL doctrine, if such a theory was one grounded in historical practice, then all of these state constitutional provisions would have been ruled as violations of the Elections Clause. They were not.

Prior Supreme Court precedent also casts doubt on the notion that state legislatures retain unqualified control over the federal elections process. In Davis v. Hildebrant (1916), decided more than a century ago, the Supreme Court ruled that the Elections Clause did not prevent voters from rejecting a congressional redistricting map in a referendum “authorized by the state constitution” (“Brief by State Respondents” 2022). Sixteen years later, in Smiley v. Holm (1932), the Supreme Court ruled that the Elections Clause did not prevent a state governor from vetoing a legislature’s preferred course of action concerning federal elections (“Brief for Respondents” 2022). And in 2019, the majority opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause explicitly stated that “[p]rovisions in… state constitutions can provide standards” that limit how a legislature can act in the redistricting process (“Rucho v. Common Cause”). All three precedents call into question the validity of the claim that state legislatures retain absolute control over the administration of the federal

elections process.

This simmering dispute came to a head when advocates forcefully argued their positions for nearly three hours in front of the Supreme Court on December 7, 2022. Attorney David H. Thompson represented North Carolina’s Republican state legislators (Howe 2022). Thompson argued that states lack the ability to place substantive limitations on their legislature’s ability to regulate the time, place, and manner of federal elections and therefore the North Carolina Supreme Court should not have struck down the newly crafted congressional map as being a partisan gerrymander violative of the state constitution (Liptak 2022).

Several justices from across the ideological spectrum appeared deeply skeptical of adopting this far-reaching argument. Chief Justice John Roberts questioned whether Thompson’s argument can be squared with prior precedents like Smiley v. Holm (1932) (“Transcript” 2022). Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pointed out that while the US Constitution identifies the legislature as the appropriate body to regulate federal elections, it is the state constitution that confers lawmaking authority to the legislature and thus makes it subject to constitutional restrictions and state judicial review:

“What I don’t understand [Mr. Thompson] is how you can cut the state constitution out of the equation when it is giving the state legislature the authority to exercise legislative power… why suddenly in this context [of the Elections Clause] do you say all those other constitutional provisions that bind or constrict legislative authority… evaporate in this world?”

(“Transcript” 2022)

Justice Amy Coney Barrett remained skeptical of Thompson’s distinction between impermissible restrictions that limit the ability of the state legislature to actually enact its desired election laws and permissible limits that merely set out a process for the legislature to obtain its desired election regulations. According to Mr. Thompson’s proposed legal test, a hypothetical provision in a state constitution that empowers the governor to veto an election law passed by the legislature would be permissible because such a provision merely sets up a proverbial “hoop that [the state legislature] has to… jump[] through” in order to enact the desired election law (“Transcript” 2022). Suppose that the state constitution, however, contained a provision that patently barred the state legislature from engaging in partisan gerrymandering. This would not be permissible because the provision imposes constraints on the actual elections-related substance that the state legislature wishes to enact into law. Drawing on her prior experience “[a]s a former civil procedure teacher,” Justice Barrett told Mr. Thompson that “it [would be] a hard line to draw” between what restrictions are permissible or impermissible under his theory

(“Transcript” 2022).

While remaining skeptical of Thompson’s more far-reaching arguments, Justice Brett Kavanaugh floated a compromise position that would give great deference to interpretation by state courts while allowing federal courts to intervene only when state courts egregiously misinterpret the law (Howe 2022).

Neal Katyal and Donald Verrilli, former solicitor generals under the Obama administration, joined the current Solicitor General of the United States, Elizabeth Prelogar, in representing the private respondents, North Carolina state officials, and the United States federal government in front of the Supreme Court. They forcefully asserted that adopting Thompson’s argument would buck more than two centuries of history and that “the blast radius” created from the adoption of the ISL doctrine would “sow elections chaos” (Liptak 2022). Solicitor General Prelogar noted that Thompson’s theory would give the legislature “free rein” to pass any election law desired without any check on this power by the state constitution or courts (“Transcript” 2022). Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch seemed more receptive to adoption of the ISL doctrine. After Mr. Katyal warned about the potential damage to democracy that could occur if the Court were to adopt a broad version of the ISL doctrine, Justice Alito responded by rhetorically asking whether democracy would be furthered by “transfer[ing]” the power of federal redistricting to “elected [state] supreme court” judges where these judges can publicly “campaign on the issue of districting” (Liptak 2022).

We will likely not know the Supreme Court’s ruling in Moore v. Harper until June 2023. Based on oral argument, it seems likely that the Court will decline to adopt the broad formulation of the ISL doctrine advocated by the Republican state legislators from North Carolina. As Justice Elena Kagan noted, a ruling that embraces much of the ISL doctrine would unleash dramatic consequences (“Transcript” 2022). State courts would be powerless to stop legislatures from engaging in aggressive partisan gerrymandering while voting rights protections in state constitutions would be vulnerable to evisceration (“Transcript” 2022). A narrow ruling that reaffirms the vital role that state courts and state constitutions play in safeguarding our federal election processes would be consistent with both historical practice and prior precedent. Such a ruling would reaffirm the role that checks and balances plays in ensuring that no branch of elected government wields more power than the rest.

Joseph Brugellis is a freshman from New Hyde Park, NY, on Long Island who intends to double-major in history and philosophy, politics, and law. After graduation, Joseph plans to go onto law school and hopes to one day be appointed as a federal judge. Joseph is passionate about the American judicial branch and is deeply interested in how different interpretative philosophies held by judges shape constitutional law. During summer 2022, Joseph worked as an intern in the office of state Senator Anna M. Kaplan. In his free time, Joseph enjoys reading, listening to music, and exploring nature.

References

Amar, Vikram and Akhil Amar. 2021. “Eradicating Bush-League Arguments Root and Branch: The Article II Independent-State-Legislature Notation and Related Rubbish.” The Supreme Court Review, 1–51. www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/720128.

“Brief by State Respondents”. 2022. Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1271/243478/20221019152815715_21-1271%20Moore%20v.%20Harper%20-%20State%20Respondents%20Brief.pdf.

“Brief for Petitioners.” 2022. Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1271/236562/20220829124545799_21-1271%20Brief%20for%20Petitioners.pdf.

“Brief of Amici Curiae Scholars of State Constitutional Law.” 2022. Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-1271/244053/20221026154758809_Moore%20Harper%20Amicus%20Brief.pdf.

“Bush v. Gore.” Oyez. www.oyez.org/cases/2000/00-949.

Chung, Andrew. 2018. “Supreme Court turns away Pennsylvania electoral map dispute.” Reuters, October 29. www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-court-gerrymandering/supreme-court-turns-away-pennsylvania-electoral-map-dispute-idUSKCN1N31PC.

Herenstein, Ethan and Thomas Wolf. 2022. “The ‘independent state legislature theory,’ explained.” Brennan Center for Justice, June 6. www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/independent-state-legislature-theory-explained.

Howe, Amy. 2022. “Court seems unwilling to embrace broad version of ‘independent state legislature’ theory.” SCOTUSblog, December 7. www.scotusblog.com/2022/12/court-seems-unwilling-to-embrace-broad-version-of-independent-state-legislature-theory/.

Liptak, Adam. 2022. “Supreme Court Seems Split Over Case That Could Transform Federal Elections.” The New York Times, December 7. www.nytimes.com/2022/12/07/us/supreme-court-federal-elections.html.

“Order List: 6/30/22.” 2022. Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov/orders/courtorders/063022zor_5he6.pdf.

“Rucho v. Common Cause.” FindLaw Cases and Codes. caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/18-422.html.

“Transcript of Oral Argument in ‘Moore v. Harper,’” 2022. Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/2022/21-1271_5i26.pdf.

You must be logged in to post a comment.